Law professor’s book unmasks ugly underside of mass torts

National News

Audio By Carbonatix

8:06 AM on Monday, January 12

Plaintiff lawyers could have done the right thing when they began seeing reports of women suffering painful side effects from pelvic mesh implants. They could have represented clients with legitimate complaints that the product, used mostly to fix pregnancy-related incontinence, was defective or overhyped.

Too many lawyers chose a different course: They spent millions of dollars on ads to recruit any woman with an implant, then flew them to shoddy medical clinics where doctors removed their implants to magnify the value of their claims. These women signed contracts putting the entire tab on them – the airfare, the hotel room, the surgeon’s inflated bill – at usurious interest rates.

By the time their cases settled, some were left with nothing while everyone else in the ring walked away with millions.

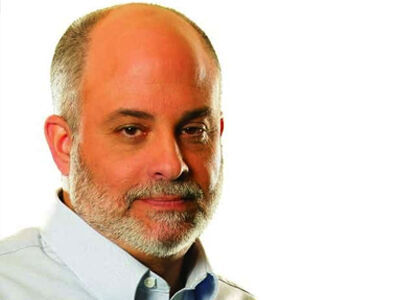

University of Georgia Law School Professor Elizabeth Burch exposes this seamy business in her new book, “The Pain Brokers.” It’s a common tale in the world of mass-tort litigation, where law firms represent thousands of claimants at once and use gaps in the rules to collect large fees while producing little of value for claimants.

“A lot of what I wrote about is already prohibited,” said Burch, who as a scholar favors using tort law to correct corporate misbehavior. “The problem is there is not regular enforcement of the law on the books.”

Most states prohibit lawyers from paying for referrals, for example, but the plaintiff lawyers in Burch’s book found a loophole in Washington D.C. that allowed them to ally with a LINO – law firm in name only – that funneled women with pelvic mesh implants to them in exchange for the bulk of any fees collected. In reality, this practice is common across mass torts, where the law firms that advertise on TV are effectively marketing operations that collect a fee for collecting names and selling them to trial lawyers.

It is also illegal for lawyers to collect kickbacks from lenders, medical providers and others feeding off tort lawsuits. But thanks to a skeptical judge in the implant case, defense lawyers used subpoenas to uncover a network that fed off women’s pain by directing them to allied doctors and lenders who financed everything.

One example: Barbara Shepard signed a contract with Coast to Coast Legal Funding for a $1,700 advance on her lawsuit against Johnson & Johnson. What she didn’t know was she’d actually borrowed $4,000, including $536 in fees to the lender and $2,300 paid to a preexisting creditor, Medical Funding Consultants, that had paid for her trip to the surgeon to have her implant removed.

The interest rate was so high she would owe $9,000 if she paid off the loan the next day. In reality, most mass-tort cases take years to settle, meaning the interest on numerous charges chews up most of what a client receives after paying the lawyer’s contingency fee, which can be 50%.

While two men ultimately pled guilty to fraudulently pressuring women to receive unnecessary surgery in the pelvic implant case, the rest of the characters in Burch’s book escaped prosecution. The ringleader of the scheme was Vince Chhabra, who’d already done time in prison for running a pill mill. The names of pelvic implant patients were obtained from data centers in India that processed insurance claims, a clear violation of U.S. law.

But while the FBI investigated and obtained two convictions, the rest of the players seem to have faded into the background.

For Burch, pelvic implants represent the dark side of American tort law, a system that enriches lawyers and the supporting characters that surround them, from unscrupulous doctors to hedge fund-financed lenders. Unlike most legal academics, Burch engages in shoe-leather reporting, actually interviewing some 150 people and digging through 200,000 court records to understand how the scheme worked.

That’s work judges, bar associations and regulators should be doing, Burch maintains. Plaintiff lawyers regularly sign unethical agreements with defendant companies under which they commit to obtaining agreements from all of their clients, for example, a clear violation of their duty to represent each person as an individual. Many also appear to have close ties to lenders who finance cases at outrageous interest rates, which they can charge since most states treat lawsuit loans as investments exempt from usury laws.

“Plaintiffs are complaining regularly and nothing happens,” Burch said. “Judges in general have the ability to look into whatever it is they want to get to the bottom of,” but don’t. Medical boards also have a “protectionist agenda,” she said, and don’t intervene even when there is clear evidence doctors are performing unnecessary procedures to inflate the value of legal claims.

Burch teaches a mass torts seminar at the University of Georgia, where she introduces students to how the system actually works, as opposed to in theory. It’s an eye-opener, she said.

“I get so many questions, because everything they’re learning in all their other classes say you can’t do this,” she said with a laugh.